Sunday, January 26, 2014

A Very Special edition of Sunday Spinelessness

Wow, it's been a long time since I wrote something here. Let's see if I can remember how this goes: I find a weird-looking bug and take some photos. Then I enthuse about that bug for a few paragraphs, hoping some broader point will emerge from all my geekery..

All right then, here's a neat creature I found recently in the Wellington Botanic Garderns. It's Helpis minitabunda the Australian Bronze Jumping Spider:

OK, so just this once the vertebrates might be the most interesting things in these photos. In November Ana, who has for many years put up with me turning over leaves and rolling rocks in search of interesting critters, and I got married. Since Ana made the most beautiful bride, and we had a wonderful day in the Botanic Gardens I can't help but share a few more photos:

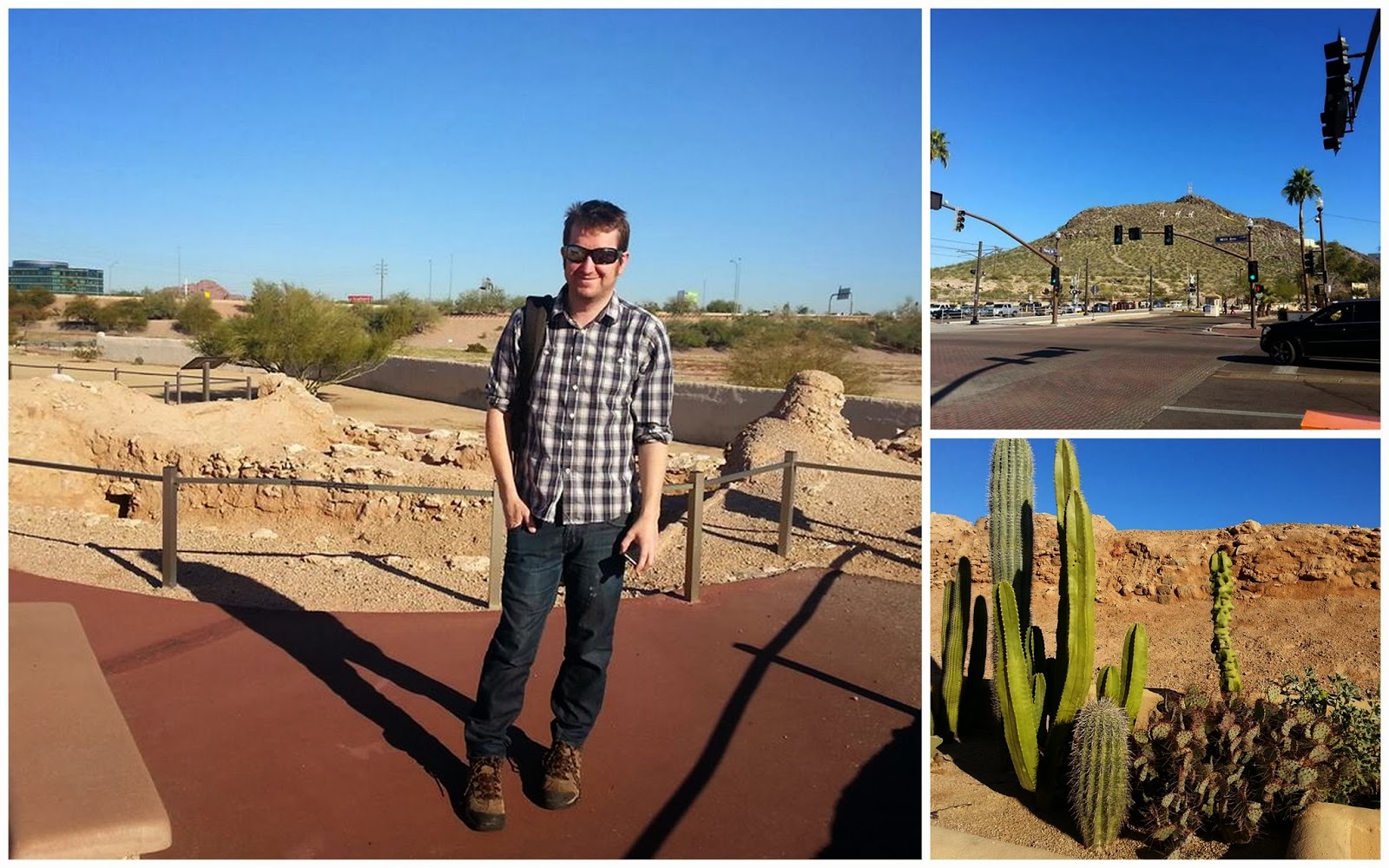

Since getting married Ana and I have set out on another adventure. We've moved from the green and pleasant land in those photos to the endless sun and aridity of the Sonoran desert:

I am a doing a postdoc with Reed Cartwright at Arizona State University, where I am working to develop new techniques for detecting mutations from sequencing data and applying those methods to a very cool experiment .

Ana and I are starting to settle in to life here in the desert (I don't think we'll really be integrated into Phoenician life until we have a car, but that will happen soon), so I hope The Atavism will spring back to life soon. There certainly shouldn't be a shortage of topics to cover - I have a whole new invertebrate fauna to nerd out over, life in the desert to learn about and a whole new science system to try and understand!

Labels: sci-blogs, sunday spinelessnes

Monday, June 17, 2013

Sequencing the tuatara genome

Things have been quite around here for a while. Largely for the typical boring reasons, the pressure to get work done and on to journals that might publish it leaving little spare time. On top of that the non-science time I've had lately has taken up by what I think will be a very important piece of science communication: a blog documenting The Tuatara Genome Poject.

I'll keep trying to find time to share my thoughts here, but I really encourage all my readers to read and follow the tuatara blog - we're going to be discussing everything from why we'd want to sequence a genome, to actual process we'll use to it and some of the results that we'll gather. I won't be writing every word, in fact, one of the goals is to get the researchers on the project to describe their work in their own words. Hopefully we'll all learn a bit about reptiles, genome sequencing bioinformatics and a whole lot more.

I'll keep trying to find time to share my thoughts here, but I really encourage all my readers to read and follow the tuatara blog - we're going to be discussing everything from why we'd want to sequence a genome, to actual process we'll use to it and some of the results that we'll gather. I won't be writing every word, in fact, one of the goals is to get the researchers on the project to describe their work in their own words. Hopefully we'll all learn a bit about reptiles, genome sequencing bioinformatics and a whole lot more.

Labels: blog blogging, sci-blogs

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Sunday Spinelessness - Mostly True Facts about land snails

The ailing laptop on which I write these posts has developed a new symptom - a non-deterministic keyboard. So, I hope you'll excuse me if I just paste a link and get on with something less annoying than trying to write a post via a cellphone.

It's a pretty good link too. Ze Frank's "True Facts" series of zoological oddities has finally got to the best creatures on earth, land snails:

Pretty much everything Frank says about snail mating is true so, laptop permitting, I'll use next week's post to expand on how anatomy and behaviour have co-evolved to give us produce these mating habits, and how they effect evolutionary processes in land snail populations.

It's a pretty good link too. Ze Frank's "True Facts" series of zoological oddities has finally got to the best creatures on earth, land snails:

Pretty much everything Frank says about snail mating is true so, laptop permitting, I'll use next week's post to expand on how anatomy and behaviour have co-evolved to give us produce these mating habits, and how they effect evolutionary processes in land snail populations.

Labels: land snails, sci-blogs, snails, sunday spinelessness

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

Darwin and New Zealand

February the 12th is the anniversary of Charles Darwin's birth.

Across the world people will be marking the day by remembering Darwin the discoverer of evolution by natural selection, Darwin the cautious husband, Darwin the barnacle boffin and maybe even Darwin the geologist who explained the origin of coral atolls. I might be the only person who takes some time today to remember Darwin as a grumpy young traveler.

Darwin visited New Zealand in 1835, and he really didn't like it.The New Zealand visit came four years into the HMS Beagle's voyage, and at the end of a four thousand kilometer journey from Tahiti. Darwin and the Beagle's crew had loved their time in Tahiti (Darwin records that "every voyager ... offered up his tribute of admiration" to the island p 416). With the memory of Tahiti in mind, the sight of fern-clad hills, a few European houses and a single waka to act as a greeting party was a disappointment for Darwin:

Now, it is obvious that Darwin meet New Zealand at a bad time. The capital, Kororareka, had well and truly earned its nickname as the "Hell Hole of the Pacific", Maori where adjusting to life alongside Europeans, and the impact of the Musket Wars and the native flora and fauna was already in decline thanks to the introduction of pests and the clearing of forests. But when you consider that Darwin was in the Bay of Islands in summer time I don't think I'm being too parochial to suggest Darwin was being just a tad grumpy when he decided there was nothing to like in our country:

He developed contacts in New Zealand and his correspondence with other scientists has many references to our plants and animals. The presence of flightless birds, bats and the effects of glaciation all come up multiple times. But New Zealand's most important influence on Darwin's thinking came via his best friend, Joseph Hooker .

Like Darwin, and many other Victorian naturalists, Hooker started his career by jumping on a ship and sailing to the other side of the world. For Hooker, that meant the HMS Erebus and trip to Antarctica via South America, New Zealand and Australia. Hooker had read Darwin's Journey of the Beagle in proof before he set off, and when he returned to England the two stayed in contact.

In 1844 Darwin "confessed" his ideas about the origin of species to Hooker. That letter contains references to the New Zealand flora, in which Darwin is fishing for facts that might support his ideas about species moving from one land to another. In the same year, Darwin started a discussion with Hooker about the distribution of Kōwhai (Sophora). The yellow-flowering Kōwhai will be familiar to all New Zealanders, but it may come as surprise that some of the "Kōwhai" species sold in garden centres aren't from New Zealand at all, but are Chilean Sophora species. The species are similar enough they'll happily hybridise given the chance.

These Chilean Kōwhai are an example of a common pattern - the floras of New Zealand, Tasmania South American and the sub-Antarctic seem to be closely related. Hooker thought this pattern arose because all these island where connected in a southern super continent. Darwin didn't like the idea of creating new land to explain a biological pattern, and instead proposed that that chance dispersal (by wind or rafting) could explain the distrbution of these species. Darwin was a keen experimentalists, and so, he set about dropping seeds in salty water and attempting to germinate them. These experiments took place in Darwin's house in Down, and apparently his children counted each germination as a victory for their dad over Hooker.

It seems Hooker couldn't provide Kōwhai seeds for Darwin's experiments, but Darwin took a record of just three equally-sized Kōwhai trees on the Chatham Islands (some seven hundred kilometers from the mainland) as evidence for long-range dispersal, and perhaps a suggestion that Kōwhai seed could survive a trip from Chile to New Zealand.

It turns out Darwin was right about Kōwhai although he got the direction wrong. Molecular studies have shown that Sophora arose in the Northern Pacfic, dispersed down to New Zealand and arrived in Chile via the Antarctic's strong circumpolar current, all in the last few million years (Hurr et al, 1999 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00302.x).

Darwin got a lot right, and foresaw many developments in the study of evolution. But evolutionary biology is much more than 21st century 'Darwinism'. Darwin didn't know what a gene was, so is unlikely to teach us much about genomics. For me, the most important thing to learn from Darwin's writing is the way he set out about understanding the world. Darwin sought out evidence for each sub-hypothesis in his Big Idea, sometimes that meant writing to colleagues like Hooker and Haast and sometimes that meant doing experiments like his salty seeds.

Darwin never got a Kōwhai seed to experiment with, but, in his 1958 lecture on Darwinism in New Zealand, AC Flemming mentioned a study that found they can survive 4 months of immersion in salt water. That's a little shorter than the time you'd expect a seed pod set adrift from New Zealand to take before it washed up on a Chilean beach. Right now, highschool students are starting another year of biology classes - and teachers are probably preparing another re-hash of the "plant study" they've taught to Year 13 students since they were called Seventh Formers. Wouldn't it be a fitting tribute if some of those classes did something a little different, and honoured Darwin's approach to undestanding the biological world by dunking Kōwhai seeds and running an experiemnt he never got to?

Quoted passages are from Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle. Links go the the Darwin Online Fascimile.

*Forget about the finches

Across the world people will be marking the day by remembering Darwin the discoverer of evolution by natural selection, Darwin the cautious husband, Darwin the barnacle boffin and maybe even Darwin the geologist who explained the origin of coral atolls. I might be the only person who takes some time today to remember Darwin as a grumpy young traveler.

Darwin in New Zealand

Darwin visited New Zealand in 1835, and he really didn't like it.The New Zealand visit came four years into the HMS Beagle's voyage, and at the end of a four thousand kilometer journey from Tahiti. Darwin and the Beagle's crew had loved their time in Tahiti (Darwin records that "every voyager ... offered up his tribute of admiration" to the island p 416). With the memory of Tahiti in mind, the sight of fern-clad hills, a few European houses and a single waka to act as a greeting party was a disappointment for Darwin:

Only a single canoe came alongside. This, and the aspect of the whole scene, afforded a remarkable, and not very pleasing contrast, with our joyful and boisterous welcome at Tahiti. (p 417)Closer inspection of the land around the Beagle's mooring in the Bay of Islands didn't do much to improve the young Darwin's opinion of New Zealand

In the morning I went out walking; but I soon found that the country was very impracticable. All the hills are thickly covered with tall fern, together with a low bush which grows like a cypress; and very little ground has been cleared or cultivated .. (p 418)And if the plants weren't enough, introduced predators had already removed much of native fauna:

I saw very few birds.. It is said that the common Norway rat, in the short space of two years, annihilated in this northern end of the island, the New Zealand species. In many places I noticed several sorts of weeds, which, like the rats, I was forced to own as countrymen. (pp 427-8)In nine days of traveling around the Bay of Islands Darwin found very little to like. In comparison to the Tahitians the Māori were "of a much lower order" (p 420) and the Europeans inhabitants where "the very refuse of society" (p 420). In fact, the only place he liked was William Williams' attempt to remake England at the Mission house in Waimate North. (pp 425-30).

Now, it is obvious that Darwin meet New Zealand at a bad time. The capital, Kororareka, had well and truly earned its nickname as the "Hell Hole of the Pacific", Maori where adjusting to life alongside Europeans, and the impact of the Musket Wars and the native flora and fauna was already in decline thanks to the introduction of pests and the clearing of forests. But when you consider that Darwin was in the Bay of Islands in summer time I don't think I'm being too parochial to suggest Darwin was being just a tad grumpy when he decided there was nothing to like in our country:

Left: Pahia beach, CC 2.0 by Fras1997 . Right: Tapeka Sunrise, CC2.0 by Chris Gin

New Zealand in Darwin's thinking

Darwin didn't think much of New Zealand while he was here, but I suspect he ended up regretting the brevity of his visit. About 30 years after he gladly left our islands behind, Darwin wrote a letter to Julius Von Haast to thank him for some information he'd provided, addingI really think there is hardly a point in the world so interesting with respect to geographical distribution as New ZealandDarwin spent a lot of time thinking about the geographical distribution of species. His first written account of where species might come from was spurred by thinking abut the distribution of Galapagos and Ecuadorian mockingbirds*. More importantly, if Darwin was going to do away with the popular idea that each continent's species arose more or less in their current place, he had to work out how plants and animals could get from one place to another.

He developed contacts in New Zealand and his correspondence with other scientists has many references to our plants and animals. The presence of flightless birds, bats and the effects of glaciation all come up multiple times. But New Zealand's most important influence on Darwin's thinking came via his best friend, Joseph Hooker .

Like Darwin, and many other Victorian naturalists, Hooker started his career by jumping on a ship and sailing to the other side of the world. For Hooker, that meant the HMS Erebus and trip to Antarctica via South America, New Zealand and Australia. Hooker had read Darwin's Journey of the Beagle in proof before he set off, and when he returned to England the two stayed in contact.

In 1844 Darwin "confessed" his ideas about the origin of species to Hooker. That letter contains references to the New Zealand flora, in which Darwin is fishing for facts that might support his ideas about species moving from one land to another. In the same year, Darwin started a discussion with Hooker about the distribution of Kōwhai (Sophora). The yellow-flowering Kōwhai will be familiar to all New Zealanders, but it may come as surprise that some of the "Kōwhai" species sold in garden centres aren't from New Zealand at all, but are Chilean Sophora species. The species are similar enough they'll happily hybridise given the chance.

These Chilean Kōwhai are an example of a common pattern - the floras of New Zealand, Tasmania South American and the sub-Antarctic seem to be closely related. Hooker thought this pattern arose because all these island where connected in a southern super continent. Darwin didn't like the idea of creating new land to explain a biological pattern, and instead proposed that that chance dispersal (by wind or rafting) could explain the distrbution of these species. Darwin was a keen experimentalists, and so, he set about dropping seeds in salty water and attempting to germinate them. These experiments took place in Darwin's house in Down, and apparently his children counted each germination as a victory for their dad over Hooker.

It seems Hooker couldn't provide Kōwhai seeds for Darwin's experiments, but Darwin took a record of just three equally-sized Kōwhai trees on the Chatham Islands (some seven hundred kilometers from the mainland) as evidence for long-range dispersal, and perhaps a suggestion that Kōwhai seed could survive a trip from Chile to New Zealand.

It turns out Darwin was right about Kōwhai although he got the direction wrong. Molecular studies have shown that Sophora arose in the Northern Pacfic, dispersed down to New Zealand and arrived in Chile via the Antarctic's strong circumpolar current, all in the last few million years (Hurr et al, 1999 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00302.x).

Honouring Darwin Day in New Zealand

I'm not quite sure how I feel about Darwin Day. There is not doubt that Darwin was a genius, an exellent naturalist and the founder of a field of study that lives on today. But there is something a bit odd about the annual veneration of Darwin, and the rush to connect modern ideas in evolutionary biology with things Darwin wrote 150 years ago.Darwin got a lot right, and foresaw many developments in the study of evolution. But evolutionary biology is much more than 21st century 'Darwinism'. Darwin didn't know what a gene was, so is unlikely to teach us much about genomics. For me, the most important thing to learn from Darwin's writing is the way he set out about understanding the world. Darwin sought out evidence for each sub-hypothesis in his Big Idea, sometimes that meant writing to colleagues like Hooker and Haast and sometimes that meant doing experiments like his salty seeds.

Darwin never got a Kōwhai seed to experiment with, but, in his 1958 lecture on Darwinism in New Zealand, AC Flemming mentioned a study that found they can survive 4 months of immersion in salt water. That's a little shorter than the time you'd expect a seed pod set adrift from New Zealand to take before it washed up on a Chilean beach. Right now, highschool students are starting another year of biology classes - and teachers are probably preparing another re-hash of the "plant study" they've taught to Year 13 students since they were called Seventh Formers. Wouldn't it be a fitting tribute if some of those classes did something a little different, and honoured Darwin's approach to undestanding the biological world by dunking Kōwhai seeds and running an experiemnt he never got to?

Quoted passages are from Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle. Links go the the Darwin Online Fascimile.

*Forget about the finches

Labels: Darwin, Darwin Day, history of science, sci-blogs, science and society

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Sunday Spinelessness - Cannibalism in the garden

The most common jumping spider in our garden, Trite auricoma, with the remains of it most recent meal... a smaller T. auricoma:

Cannibalism, animals eating members of their own species, is a pretty common and widespread behavior. Species in almost every phylum have been shown to occasionally (or frequently) eat members of their own species. Even herbivores like monarch butterfly caterpillars will eat any monarch eggs they encounter.

In spiders, the most well-studied form of cannibalism relates to mating. In a very few species male spiders will offer themselves as a meal to their mate. In so doing, males make sure their offspring get the best start in life, by providing their mother with a nutrition meal. They are often also posthumously rewarded by female, who reject other suitors and ensure the sacrificial male's legacy. The best example of this behaviour comes from the Australian red back spider (Latrodectus hasseltii). In this species males actually pirouette their way into their mate's fangs, and females take up the offer about 65% of the time. New Zealand's endemic red back relative, the katipo, does not exhibit this behavior (nor does the North American black widow, despite the name).

Such sexual cannibalism isn't known from jumping spiders (although females will certainly eat unwary males), and a wider (and earlier) shot lets you see that this was a case of a mature spider taking a younger one (males and females are about equally sized in T. auricoma).

Cannibalism, animals eating members of their own species, is a pretty common and widespread behavior. Species in almost every phylum have been shown to occasionally (or frequently) eat members of their own species. Even herbivores like monarch butterfly caterpillars will eat any monarch eggs they encounter.

In spiders, the most well-studied form of cannibalism relates to mating. In a very few species male spiders will offer themselves as a meal to their mate. In so doing, males make sure their offspring get the best start in life, by providing their mother with a nutrition meal. They are often also posthumously rewarded by female, who reject other suitors and ensure the sacrificial male's legacy. The best example of this behaviour comes from the Australian red back spider (Latrodectus hasseltii). In this species males actually pirouette their way into their mate's fangs, and females take up the offer about 65% of the time. New Zealand's endemic red back relative, the katipo, does not exhibit this behavior (nor does the North American black widow, despite the name).

Such sexual cannibalism isn't known from jumping spiders (although females will certainly eat unwary males), and a wider (and earlier) shot lets you see that this was a case of a mature spider taking a younger one (males and females are about equally sized in T. auricoma).

Labels: arachnophilia, environment and ecology, jumping spiders, photos, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Elsewhere

A couple of links that might be of interest for readers of The Atavism:

- I've been really remiss in linking to interview I did with Veronika Meduna for Radio NZ's Our Changing World. The bugs Veronika and I visited will all be familiar to readers here

- The online Evolutionary Biology Journal Club is getting back together for "Season 2". If you don't know, a journal club is basically a bunch of geeks getting together to discuss recent (or no so recent) papers in a shared area of geekiness. As the first paper in this season's line up is one I already know pretty well I wrote a quick summary of it to serve as a jumping-off point. The discussion will be on Tuesday morning NZ time, and anyone who is keen can jump in (and if next week doesn't work there will be plenty more sessions this year).

Labels: blog blogging, sci-blogs

Sunday, January 27, 2013

Sunday Spinelessness - Native bees again

Last year, at about this time, I wrote a little about our native bees. Though I'm glad to have done my little bit to promote the existence of these all too anonymous members of our natural heritage I've always felt a little embarrassed by the photos in that post. As I admitted at the time the photos are staged. Photographing our twitchy little bees is hard - apart from being small, they zip about from flower to flower much more quickly than I can line up, let alone focus, shots.

So, to illustrate the original post I used half-drowned bees, scooped out from a swimming pool. The time it took the bees to dry out gave me a chance to take the photos, but I set them up on exactly the type of flower they'd never visit in the wild. So, not only did I cheat, but the photos I took actively misled about the true nature of bees!

So, here are some much worse photographs of native bees that do a much better job of representing their lifestyles. First off, a bee perched on a favourite flower, a hebe, and deciding on its next move:

So, to illustrate the original post I used half-drowned bees, scooped out from a swimming pool. The time it took the bees to dry out gave me a chance to take the photos, but I set them up on exactly the type of flower they'd never visit in the wild. So, not only did I cheat, but the photos I took actively misled about the true nature of bees!

So, here are some much worse photographs of native bees that do a much better job of representing their lifestyles. First off, a bee perched on a favourite flower, a hebe, and deciding on its next move:

and another collecting pollen from the same plant:

These hebes, and a few parsley plants left to go to flower, make my parent's house in the Wairarapa a mecca for native bees. They certainly make their mark around the garden, if you don't notice them drowned in the pool or visiting flowers you can see their nests in the soil:

Labels: bees, environment and ecology, native bees, photos, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness